Listener – March 24, 2007

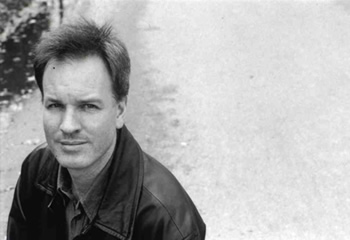

Language and literature run in poet Andrew Johnston’s family. His father was an English lecturer and his grandfather a newspaperman. After 10 years in France, Johnston has come home and published a new book, Sol, which includes “The Sunflower”, a long, impressive elegy to his father.

In 1995, Andrew Johnston had an epiphany on a street corner in New York. “I came to the realisation,” he says, “that I enjoyed being in the world a lot. I realised that whatever fears I had of somewhere like New York, the big bad city, were pretty much ludicrous, and that I loved being there.”

Johnston was in the US doing the three-month International Writing Programme in Iowa, and an encounter there was the catalyst for him to continue “living in the big wide world”. He met Christine Lorre, a Frenchwoman doing her PhD thesis on writer Clark Blaise, the director of the programme. They stayed in touch. She was living in Canada the following year, and he visited her. “After that, we didn’t think we could make a go of it, because I mean, she was going to go back to France and I was living in New Zealand.”

But love found a way. The couple travelled in the US for a month at the end of 1996, and then Johnston went to London where he worked as a subeditor on the broadsheets for eight months. Lorre joined him, and they spent the summer together in London. Then they moved to Caen in Normandy – Lorre had a teaching job there. But Johnston couldn’t get work in France, because he didn’t have working papers.

“I fell back on plan B, which was to commute once a week to work at the Observer. I did this crazy thing where I caught an overnight boat to Portsmouth, then caught the train up to London, where I worked a double shift on Friday – from 10 in the morning to 11 at night – and then I worked all Saturday, got back on the train, caught the night boat, and got home at 7.00am on Sunday. I did that for 16 months, through two winters and a summer.

“So I went through quite a few force eight, force nine gales, because the ferries just keep going. Fortunately, I’m a good sailor, as they say. I got a bit of writing done, but I was very tired as well, because that was physically quite difficult.”

The couple married in 1998, which gave Johnston the right to work in France, and he got a job on the Paris-based English- language newspaper the International Herald Tribune. He has taken a year’s leave from his job as the deputy editor of the opinion pages, and he and Christine and Emile, their five-year-old son, are living in Wellington while Johnston writes a book about contemporary New Zealand poetry – an assignment for which he was awarded the 2007 J D Stout Fellowship at Victoria University.

The fellowship has coincided with the publication of Sol, his fifth book of poetry. The book’s centrepiece, “The Sunflower” (published in the Listener earlier this year), is an impressive elegy to his father who died in 2004, and another long poem, “Les Baillessats”, is dedicated to his son. There are also poems about Paris, the natural environment and found language.

Johnston is a meticulous craftsman and a serious student of poetic form. As well as his day job he edits the Page, an e-zine with links to online poems and essays. He says that much of what informs his poems remains invisible in the finished poem. “Most poems go through at least 50 drafts, and I hold on to most for years before I let them go. I forget who it was once titled a poem ‘Poem in Memory of an Earlier Poem’. All mine could carry that title!”

Andrew Johnston was born in Upper Hutt in 1963. He is the fifth boy in a family of six and they moved to Lower Hutt when he was six. He wrote about that experience in his first book, How to Talk, which won the 1994 New Zealand Book Award for Poetry and the Jessie Mackay Best First Book Award. “A big event like that means you have distinct memories.”

His father was an English lecturer at Victoria University, and did two terms as Pro-Vice-Chancellor. “He taught all sorts of things,” Johnston says. “He taught a lot of American literature, mainly the novel. He didn’t really teach poetry, except if it was part of a stage-one course. His favourites were Henry James and Joseph Conrad, neither of whom I’ve been able to read, because when I was about 10 if I said I was bored he would go into his study and get a Henry James, and say, ‘Here, read this.’ And I couldn’t, because it was too hard for me. And it created a kind of block, which I’ve had since.”

But there was plenty to read in the Johnston household. “We had some great books at home – The Oxford Book of Poetry for Children, the purple one, with wonderful illustrations. My uncle, my father’s brother, who was an English lecturer in Australia, sent us an anthology called Four Corners, which had two little 45 records of the poems being read, tucked in the back cover. I loved those two books from very early on.”

Johnston started writing poems at St Patrick’s, Silverstream. “I had some wonderful English teachers at that school. I wrote poems in the third and fourth form. At that stage, there was an annual anthology of poetry by secondary students. I don’t even know if it exists any more. I think it was published out of Christchurch Teachers’ College. That was the first thing I strived to get into. I loved it. And I was in a few of those. That was the thing that I got the biggest kick out of as a teenager.”

His university years, he says, were “quite muddled”. He changed what he was doing almost every year. “I did medical intermediate at Victoria University, including English, because I was allowed to do an arts paper, and I went down to Otago, and I did second-year medicine, but I didn’t like it. I realised that wasn’t what I wanted to do. I wanted to write. So I switched to a BA in English. Then in 1984, I took a year off to edit the student news-paper, Critic, which in terms of the rest of my life was probably the most significant thing that I did … Then in 1986 I went up to Auckland and did a one-year MA in English … As part of that MA, I was able to do the creative writing paper that C K Stead taught. In fact, it was his last year of doing it, and he retired in September that year.”

After a short stint overseas, Johnston was “lucky” to get a job as a subeditor on the Otago Daily Times and was trained on the job. He worked there for a year and moved to Wellington in the late 1980s to work on the Evening Post, then in the features department of the Dominion, where he worked with Patrick Ensor, “a very good UK journalist, who really taught me to edit. He gave my work back to me with red marks on it, showing how he would fix things up, and that was a great education.”

For five years, until he left for overseas, he edited the books page on the Evening Post. “I worked 20 hours a week and I could go in whenever I liked, as long as I did my 20 hours and the page came out. So for a poet it was fantastic.”

THERE IS A BIT IN “The Sunflower” where Johnston is addressing his dead father that begs a bigger story:

You talked and talked, as you’d always done, of all but you, till you were out of breath. I would have liked to hear – despite your fear of theatre (so foolish was I, and ignorant before thee) – about your mother, for instance, who took to bed when tempers rose; and how the sun had burned a deadly thirst into your father’s breath …

Frank Johnston, who emigrated from Scotland in the 20s, worked on the Dominion as a subeditor and editorial writer in the 1940s and 50s. “The sad thing is, my father didn’t talk about him much.I don’t think my father had a particularly happy childhood. My grandfather was a drinker. I think that the house was a pretty difficult place to be, because Frank worked nights, and they drank every night on the subs’ bench.

“I have a photo of the subs’ bench – a photo of the staff at night in the office – and Alex Veysey is one of them, and they’re surrounded by bottles. There must be a couple of dozen empty beer bottles around a half-dozen of them. Frank died of a heart attack in 1956.

“The great story is everyone thought he was 62, but his widow, my grandmother, had to send to Scotland for his birth certificate so she could get a pension. The birth certificate arrived to show that he wasn’t born in 1893. He was born in 1901. So everyone, including her, thought he was 62, but he was 54. The story is that he changed his age to fight in World War I.

“We’re trying to find out more about Frank, because like a lot of immigrants, some of those stories he told about himself don’t check out. I think he said he had a university degree from Aberdeen, but we can’t find any record of that. So that may have been a fabrication.”

Johnston talked to Veysey about his grandfather and he told him a few things. “But Alex was such a gentleman that if there was anything darker, perhaps he may not have wanted to say. He did say that they all drank a lot. He said that the subs’ bench would get through a crate of beer and a bottle of whisky every night.

“Those were different days. It’s good that it stopped; it was pretty hard on the families. So when my father was at home, his father worked nights, and then during the day would read a big stack of papers from all round the country, so the kids were obliged to be quiet. I guess Frank was grumpy as well, the way drinkers are. So my father just got out. He would go for long, long walks around the waterfront.”

It occurred to Johnston as he was gathering poems for Sol “that the sun shone through a surprising number of them – the sun and that syllable, sol, which is also in the words solitude and consolation. It would be true to say that I’m preoccupied by the way each of us is essentially alone, in the sense that no one else can hear what we’re thinking, but also by the way language can bridge, however faultily, that gap between us. As for consolation, I like that way the word means that we seek solace – from whatever – together.”

SOL, by Andrew Johnston (VUP, $25)