The Dominion Post – April 15, 2006

There was a little glue-sniffing guy who frequented Wellington’s Cuba Street in the 1980s. His alienated intelligence and limpy gait set him apart from the street kids he hung out with. He was belligerent and compassionate, toxic and sort of interesting. He disappeared from my orbit until I came across him in Manners Plaza drinking plonk and arguing with a couple of grizzly old drunks in the late 1990s. Sleeping rough and substance abuse had ravaged him, and I guess he was only in his early 30s. I don’t know his name. I gave him a wide berth. God knows what happened to him.

British writer Alexander Masters first came across Stuart Shorter in Cambridge, England, in 1998. Shorter was begging in a doorway. He told Masters, who was working for a homeless shelter: “Yeah, I’m gonna top meself and it’s got to seem like someone else done it . . . I’ll taunt all the drunk fellas coming out the pub until they have to kill me if they want a bit of peace . . . Me brother killed himself in May. I couldn’t put me mum through that again. She wouldn’t mind murder so much.”

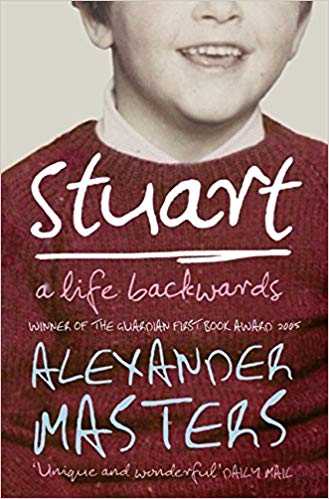

When they met a year later Masters started writing “the little nightmare’s” story. Stuart: a life backwards is one those rare books that is truly original. It is the most moving – possibly the best – biography I’ve read, although Stuart didn’t like Master’s first draft. He thought it was “bollocks boring” – he wanted a bestseller “like what Tom Clancy writes”. He suggested that Masters “do it the other way round. Make it more like a murder mystery. What murdered the boy I was? See? Write it backwards.”

We travel from the “chaotic” homeless man to a “happy-go-lucky” little boy who was born with an inherited form of muscular dystrophy, which caused him to “waddle like a goose”. “What murdered the boy” is pretty rough. Stuart was sexually abused by his brother and the babysitter, and after he demanded that his mother put him into a boys’ home, he was buggered by a caregiver. But Stuart reckons what really murdered the boy was the day he discovered violence; the day he head-butted a bully for calling him, among other things, Spaghetti Legs. From that day “Stuart realised he was no longer in charge of his mind”.

Apart from being a portrait of a poly-addicted alcoholic, who first went to jail for threatening to kill his infant son, and who developed “a Jekyll and Hyde personality with delusional paranoia and a fondness for . . . knives”, Stuart is also an endearing story of a remarkable friendship between a biographer and his subject. Some of their conversations are hilarious. Masters says, “If Stuart’s a freak, I salute freaks”. Stuart didn’t see his biography published. He was killed when “he stepped in front of the 11.15 London to King’s Lynn train”. He was 33 years old.