Listener – June 16, 2001

“Who are you? A poet or prophet or what?” This question the poet John Caselberg recalls was Colin McCahon’s first utterance to him when they met in McCahon’s studio in Christchurch in 1948. Caselberg was then 22 and McCahon was 29, and this meeting was the starting point of the most remarkable collaboration in the history of New Zealand art.

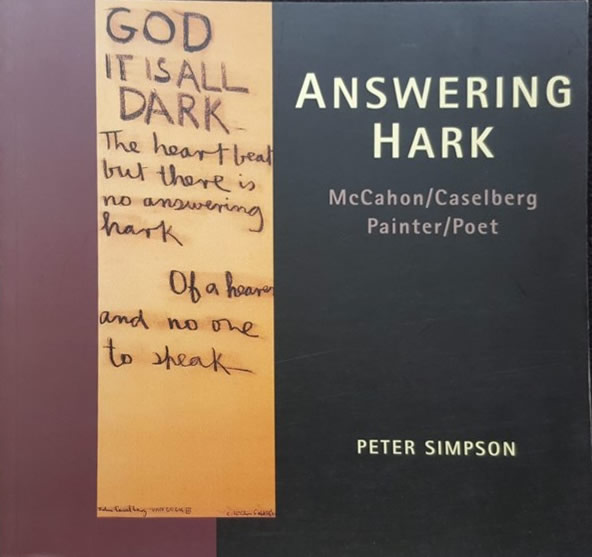

Peter Simpson points out in the opening chapter of his wonderfully moving book, Answering Hark, that in making this remark McCahon was probably subconsciously referring to himself. At the time of their meeting Caselberg was already an admirer of McCahon’s work and McCahon soon became a staunch, though not uncritical, supporter of Caselberg’s writings, which he used over the ensuing years to lighten his dark abstractions.

Through correspondence from 1950-1980 between the little-known poet and the painter who was to become a giant in antipodean art, Simpson has drawn together an insightful and sensitive account of the men’s intellectual and emotional friendship. And he has done so without sleuthing intrusively into their personal lives.

It is hard to imagine that such a collaboration would be possible nowadays. As feminist artist Barbara Kruger says, “We don’t need another hero”. The correspondence was at times painfully earnest and Caselberg’s poetry in parts elaborately woven, but McCahon drew out word by word its emotional nuances, lovingly illuminating each wrought stanza. From Caselberg’s poem about the death of his Great Dane dog in the multi-paneled The Wake, and his Van Gogh poems, to the second Gate series (dealing with nuclear holocaust), there was an unflinching belief in each other’s compassion and vision. Their manifesto “On the Nature of Art”, jointly written in 1953, is published in Answering Hark for the first time. A bold document, it tackles such matters as “how art relates to life and nature, where art originates, the relationship between subject, message and form, and the question of audience and communication – all in a highly rhetorical and metaphorical manner.”

Caselberg and McCahon believed it was their duty as artists to be lights in the darkness. Caselberg “held to the bardic tradition of vision and prophesy typified by William Blake” and McCahon said that “words were necessary to get his message across”. He wrote in a letter to painter friend Patricia France that “poetry, before painting, is my friend. The one without the other can’t exist”.

McCahon also illustrated Caselberg’s poems, plays and books, and Caselberg in turn advised McCahon on Maori language and history and supplied him with excerpts from the Bible. One surmises they were aware, long before others, that we cannot look at the landscape through eyes whose vision is not coded and that their homeland is layered with Maori history and Christianity.

In a letter by McCahon to Caselberg, when the latter was in Europe, he wrote: “Our folk art is signwriting and early watercolour drawings and that’s as far back as we go. The extent of our tradition. I don’t feel that much was carried out here from England by the settlers. It leaves a lot of freedom . . .”

While McCahon, who died in 1987, has been canonised in high-art quarters, Caselberg has been ignored by our literary anthologists. Simpson considers that it was not so much the quality of his writing that put them off, but rather that it was “against the grain of what was currently fashionable or critically acceptable”. Answering Hark brings him out of the wilderness.