Listener – June 17, 2000

Jim, Jacquie and Baxter

When I rang for an interview Jacquie Baxter asked: “What hat am I to wear – J C Sturm or Jacquie Baxter?” The answer, of course, is both. The widow of the country’s most famous poet and the woman who has become a poet in her own right are one and the same, inseparable. Testimony to that can be found in her new book of poems, which is about to be published.

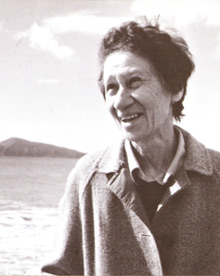

Jacquie Baxter is loose of limb and thin, her features birdlike. She has been mistaken from the back for a young girl walking along The Parade at Paekakariki, where she lives near her children and next door to her second husband, retired academic Peter Alcock. She had a book of short stories published in 1983, but established herself as a poet with Dedications (1996).

In that volume, which won a Poetry Honour Award at the 1997 Montana New Zealand Book Awards, there were poems dedicated among others to both husbands, to children Hilary and John, to writer friends Jean Watson and Janet Frame, her mother Mary Papuni and her adoptive parents Ethel and Bert Sturm. It was illustrated by James and Jacquie Baxter’s son John, who has has been establishing a reputation for himself as a Maori artist.

Now, also illustrated by John, comes a companion volume, Postscripts (Steele Roberts, $19.95).

“When I had finished Dedications,” says Jacquie, “I still hadn’t finished what I had to say. That’s why I’ve called the second book Postscripts. It has the added meaning that sometimes when you write a letter the thing you really want to say you add as a postscript.”

In Jacquie Baxter’s house everything is neatly placed. Piles of papers and used envelops. On the wall a drawing of James K done by John from an Ans Westra photograph. Dominating the room, it depicts the bard in his latter years, long hair and beard, with a rather large crucifix on his chest.

As his literary executor Jacquie makes an arbitrary distinction between the domestic person and the artist. “It’s not easy and I have to be careful I don’t take liberties with one because of the other.

“In the case of Jim, particularly since he died, I have made that distinction in order to cope with some of the requests I have had to use his work. I refer to him as Baxter when I’m talking about the artist, and Jim when I’m talking about the man who was my husband and the father of my children. It doesn’t mean anything to anyone else, but it makes sense to me.

“There are maybe things about one that I like or don’t like, which don’t apply to the other. If I don’t get them confused it’s easier for me to say yes or no impartially to permission requests.”

Is Baxter’s fame a hindrance or a blessing to the family? “Of course it’s a hindrance. More so for John than for me. It’s terribly hard to be your own person . . . to grow up like a mushroom under a mountain. It’s terribly difficult. It’s a man’s world, so people are more likely to look at the relationship between father and son if they are moving in the same direction. The comparisons are inevitable. It’s the way people think.

“My attempt to be my own person came much later in life and therefore was less important to me. Other things like bringing up a family and surviving kept me occupied. But for John when he was young it was very difficult. John has written some good verse, Jim’s brother (Terry) has written some good verse, Jim’s girlfriend wrote some good verse. But when we all got to know Baxter the poet we had to stop. John’s always had this artistic drive in him, even as a little boy. He switched to things he could do with his hands as Jim’s brother did earlier.”

Jacquie’s mother died when she was 15 days old. She spent the first two and a half years of her life with her “mother’s mother” in Taranaki and Ratana Pa but was given to foster parents when her mother’s mother became very ill – hence the name she uses as a poet.

“The Sturms were wonderful people. They gave me every opportunity and kept me on at school beyond school leaving age. They didn’t have to do that.

“When my time started with them, Mr Sturm was an auctioneer (in fruit and vegetables) in New Plymouth. He had a very good head for business and figures and did very well. I wasn’t the only one they had fostered. I was just the end of the line. And after they had taken me over as a more or less permanent fixture the Depression hit and Mr Sturm went bankrupt and lost everything, and from then on it was a struggle.”

They left Taranaki when Jacquie was six and “roamed around a bit”: Auckland, Hastings, Palmerston North, Pukerua Bay, Napier. Jacquie was sent to Otago University when she was 17 by the Health Department to study medicine. It was during the war and bright young Maori were targeted to be role models. Jacquie wasn’t suited to the subject and switched to arts, eventually graduating with an MA in Philosophy.

She met Baxter and they married in their early 20s. “When Mrs Sturm first met Jim she said, ‘You should look after him, he looks like an unmade bed.’ Jim’s mother used to buy all his clothes before we were married. I remember giving him some money to buy a coat. He came home with one that was far too big. He bought the first one the shop assistant handed him.” (Though this, she adds, was partly due to his socialist upbringing – “He didn’t like the servant/master aspect of shopping”.)

When the Baxters moved to Wellington in the late 1940s Jacquie became involved with the Maori Women’s Welfare League and joined Ngati Poneke. “I remember when John was in the pram (Hilary was three) he used to come to Ngati Poneke with me. He would be hearing haka and action songs. I believe in the importance of early childhood experience. I think they formed a bottom layer of Maoriness in him, if you see what I mean.

“When I went to hui I couldn’t take the children with me. Jim used to look after them. Jim used to come to Ngati Poneke as well, but he was very, very nervous. He’d just sit on the sideline, although he got to know the aunties, but he didn’t take an active part in those days. But something rubbed off I guess.

“When John was in standard five all four of us decided we’d take formal Maori language classes. We had a wonderful year and John was the star of the class. He has an ear for language. When we went to India (1958-59) he was the only one who learned to speak anything that mattered. I think he took after his grandmother (Millicent Baxter) in that respect. Hilary was alright. I passed. I’m not sure Jim did laughter.”

The five months spent in India, Jacquie says, changed Baxter. “It confirmed him in certain directions. The road to Jerusalem started in India.”

When Baxter went to Jerusalem, the family broke up. She herself worked for a short time at McKenzies department store before getting a job at the Wellington Public Library in 1969. By the time she retired in 1992 she had become librarian in charge of the New Zealand Room.

Baxter’s spiritual and artistic journey ended in Jerusalem. It seems now that his wife and son are artistically beating a track back to Taranaki – both have had work accepted for an exhibition exploring the Parihaka story at the City Gallery in Wellington later this year. Three poems in Postscripts tell the Parihaka story.

“Making contact with my blood relatives wasn’t easy. In order to do that I had to go back to where I was born and my mother is buried, and then to where my sister was bought up, where my father and his mother are buried. It wasn’t a conscious seeking after Maori culture, which I had been moved away from when I was a very young child. That didn’t come into it, except that when you move back for whatever reasons, things happen to you that you hadn’t planned. And so it was for me”

And her poetry? “What I have to say determines how I say it. I haven’t any great technical skills. When you study Baxter you realise how many technical skills the man had. The best of Baxter is the best we have had. It wasn’t all ideas in the night. There was a lot of hard slog. When I write I try to digest the indigestible. An that’s hard enough for me.”

When it was put to her that in the poems James K wrote to her and the ones she wrote to him there is an intensity of love and respect in operation she replies: “I would like to think so.”