Landfall Review Online – April 1, 2016

‘The Dreaming Land,’ said Martin Edmond at the launch of this memoir at Wellington’s Unity Books, ‘had its genesis in a failed manuscript.’ He’d set out to write a book about his parents’ early years together, ‘But it hadn’t worked for the obvious reason,’ he says: ‘I wasn’t there.’

He did, however, salvage two sections from the manuscript that did work: one, ‘Barefoot Years’ (initially published as an excellent wee book in BWB Texts), opens The Dreaming Land, and the other, ‘What Instruments We Have Agree’, ends Histories of the Future (2015), a Tasmanian-published collection of Edmond’s inventive prose works illustrated with his partner Maggie Hall’s evocative black and white photographs, and lauded ‘a triumph of originality and daring’ by Peter Pierce in the Sydney Morning Herald. The piece imagines his mother, poet Lauris Edmond, dying alone, aged 75, on 28 January 2000 (the 61st anniversary of W.B. Yeats’ death) in her Oriental Parade home overlooking Wellington Harbour: ‘beyond is the green valley where she once lived with her husband and their children …’

‘It is,’ Edmond says, ‘my last word on Lauris.’ So it was serendipitous then – having arrived early for the book launch I had spent some time sitting on a seat on the Para Matchitt totems-and-taniwha-adorned City to Sea Bridge idly watching rowing crews coming and going in the lagoon – that my gaze happened upon the ‘concrete’ stanza from Lauris Edmond’s poem ‘The Active Voice’, one of the works that makes up the Wellington Writers Walk: ‘It’s true you can’t live here by chance, / you have to do and / be, not simply watch / or even describe. This is the city of action, / the world headquarters of the verb.’

In the last section of The Dreaming Land, Martin Edmond, a ‘self-described flaneur’, recalls an argument with his mother after she had accused him of idleness, ‘a great sin in her eyes’:

‘What was I supposed to be doing?’ I asked. ‘Well something,’ she said, with the frustrated wave of her hands she made when the words wouldn’t come. ‘I am doing something,’ I said, not without pomposity, ‘I’m thinking.’ ‘Oh!’ she said angry now. ‘Thinking isn’t doing, it’s thinking.’ But I did not agree with her then, and I do not agree with her now: thinking is an activity like any other, just as worthwhile as going for a run, taking the dog for a walk or playing a game of tennis. On the other hand, my eldest sister once observed that I spent most of my childhood and adolescence ‘mooning around’ and no doubt she was right.

‘Mooning around’, in a positive sense, has been productive for Edmond. His book Dark Night Walking With McCahon (2011) imagines/traces the route the renowned artist (afflicted with an alcoholism-related neurologic disease) might have taken when he wandered off to lose himself in inner Sydney for 24 hours. To leaven the thought-provoking conceit, Edmond, who has lived in Sydney since the early 1980s, symbolically employs the Stations of the Cross as route points, thus rendering Colin McCahon a suffering/redemptive Christ. He spends a sleepless night under the stars in Sydney’s Centennial Park where police found McCahon whom they mistook for a homeless man. The book ends across the Tasman in Ohakune, where Edmond was born in 1952.

Crossovers of material, albeit in different contexts, appear in some of his books. Big life events in The Dreaming Land (touted as his first full-length memoir) can also be found in The Autobiography of My Father (1992) and Chronicle of the Unsung (2004): a younger sister’s suicide, his father’s breakdowns and descent into alcoholism, which directly corresponded with the flowering of his mother’s academic and literary aspirations. His father, Trevor, ‘a good man’, became troubled when he made the move from gifted classroom teacher to headmaster; and his mother, with whom he had a complicated relationship, came into her own when she went back to university and resumed ‘a literary career interrupted for twenty years by the demands of birthing and raising six children’.

As a teenager, Edmond, the third-born and only boy, ‘joked and flirted with [his] mother in a way that disturbs [him] now’, and his father’s ‘predicament filled [him] with impotent despair’. He binge-read, and at one point developed an unhealthy habit (‘it ended long ago’) of ‘taking library books and not returning them’. One such book was Henry Treece’s novel Oedipus (1964), which, with an inflated sense of entitlement, he ‘had to have’:

I was, after all, watching the slow disintegration of my father’s mind and body, though not perhaps the death of his soul; and continued to indulge, if that’s the word, an oddly ambivalent, flirtatious, if not exactly incestuous relationship with my mother. For me, however, then Oedipus was about uncovering the secret of beginnings.

The Dreaming Land travels: from Burns Street, Ohakune, in the volcanic Ruapehu district, where the family lived during the 1950s, to Main Street, Greytown, in the Wairarapa, where they resided in the upper floor and back lean-to of the Greytown Pharmacy, to Huntly in the Waikato, where they lived in the schoolhouse on ‘Nob Hill’ (Trevor Edmond was headmaster of Huntly College), and to 401 Fergusson Drive, ‘a wealthy enclave’ in Heretaunga, Upper Hutt, the aforementioned ‘green valley’, from where the 18-year-old Martin Edmond left to attend Auckland University.

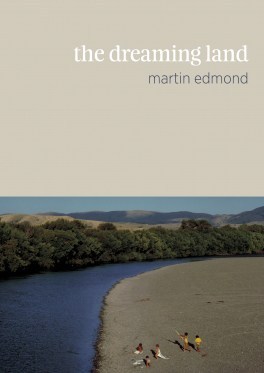

Four homes, four sections, titled: ‘Barefoot Years’, ‘Main Street’, ‘Taniwha Rau’ (Māori mythical monsters and the name of the Huntly Rugby League Club) and ‘Abdulla 9 & 37’ (an English brand of blended cigarettes Edmond smoked: No 9 being Turkish and No 37, English). The cover photograph by the late Robin Morrison shows an elevated view of swimsuited children playing on a gravelly riverbank; the opposite bank is treelined and the denuded background hills bring to mind the hills McCahon depicted overlaid with Biblical texts. The back cover blurb informs: ‘The Dreaming Land shows us the making of a thinker and a writer.’ And the pull quote highlights the eloquence of Martin Edmond’s prose:

So here I am walking again an old path made new by the very fact that I am upon it once more, accompanied by familiar hordes: the fecund majority of the dead, the myriad of the living in all their many forms, defunct, mutant, revenant or otherwise, traversing memory’s infinite field.

Edmond’s first career ambition was to be an archaeologist, which he practised by reciting the names of the geological periods. The ambition was perhaps seeded in the sandpit, where he ‘spent uncountable happy hours constructing towers, pyramids, mountains, cities’:

The greyish-yellow volcanic sand [was] gathered from a particular spot on the banks of the Whangaehu out past Karioi, where we go on occasion in the car with the trailer attached behind to renew our supply. The swift, turbid, sulphurous river, flowing directly from the crater lake on the mountain, fills us with terror, but the sand itself is a blessing and a boon; later on my parents liked to recall I spent so long engrossed in my games in the sandpit that I poo myself and hardly even notice I had so. And now, as I write, I remember again the soft lumpy protuberance of a turd in my pants …

Most would jettison that last sentence, but it shows commitment in connecting with his young self. In his little book-length essay Ghost Who Writes (2004), Edmond likened good writing to: ‘Lucid Dreaming or true dreaming’, which I take to mean ‘being in the world, but not of it’, which is a Christian saying that has become secular in meaning. This ‘dreaming’ allows the storyteller to be a character in his own creation, which is made explicit in the following sentence, describing part of the ‘wonderful old garden’ in which the Burns Street house, ‘the original Memory House’, stood:

I like the pansies best, because they remind me of faces, sometimes cheerful, sometimes sinister, sometimes merely thoughtful, looking up at the small boy looking down at them.

On one level The Dreaming Land is a series of self-portraits: The Nerd, The Reader, The Observer, The Anglican Altar Boy, The Loner, The Rugby Player, One Of The Lads, The Tortured Adolescent, The Top Student, The Hip Young Man. And throughout the book is the ghost of Edmond’s sister, Rachel, with whom he was very close, and who, like him, was secretive, ‘but she would take her secrets to the grave’. He recalls a family hiking trip to a hut partway up Mount Ruapehu, and being woken by her cries after she had fallen out of the bunk above his:

I never went back to the old Blyth Hut, which was burned by hoons in the 1990s; never once climbed higher than where it stood on Ruapehu. And yet, again and again, I dream of how the cloud parts and I see the gigantic, snow-gashed side of the mountain looming. Always I am climbing into a maelstrom of snow and ice, always I am in the company of my sister; inevitably there comes a point when my heart fails and I cannot go on; when she tears her hand from mine and goes on alone, disappearing towards the summit of whiteness, that beyond with no beyond.

If ‘Lucid Dreaming’ is instrumental in recalling emotional detail, then Edmond’s long-time interest in poetry, history, philosophy and the visual arts has given him the skill to frame colourful vignettes of 1950s Ohakune. We are taken to the remnants of the old shopping district burned in a fire in 1917 and …

the depot for the market gardens owned and operated by Chinese Maoris, specifically the Sue Joe family; their red sheds, their blue tractors, their battered paintless Bedford truck; their many fat and smiling children of different sizes and sexes, like babushka dolls unfolded out of some obscure genealogies.

And I’m taken back to the City to Sea Bridge and the Para Matchitt poles, which elevate a five-pointed star and phases of the moon, inspired by the flag used by Māori prophet Te Kooti, when I read:

… the run-down weatherboard houses in Moore Street have the tops of the pickets on their fences carved with hearts, diamonds and spades from the playing-card deck, or five-pointed stars within the cusp of a crescent moon. The paint – blue, white, purple, red, gold – is peeling from these symbols of Te Haahi Ratana, the Ratana Church, whose local place of worship, with its twin towers inscribed Arepa (Alpha) and Omeka (Omega), is on a hill outside the next town, Raetihi.

Edmond has been diligent in researching tangata whenua history in the districts in which he and his family lived. While Māori and Pākehā were schooled and played sport together, when it came to Māoritanga the cultures lived separate lives. Edmond grew up with framed prints of paintings by van Gogh, Gauguin, Vermeer and Manet, original works by Ivy Fife and Noeline Bruning, and a children’s painting by Colin and Anne McCahon:

All of these pictures, which I saw, as a child will, purely in visual terms, were like shards from the broken world of the Burns Street house; but they were also, if such can be, windows back into that gone world …

The pictures also hung in the Greytown and Huntly houses, but when the family unpacked in Fergusson Drive they were relegated to a wardrobe shelf. Later Edmond ‘retrieved those I still have’. He attended Heretaunga College where his father was headmaster and his mother his English teacher, ‘and a good one too: enthusiastic and energetic with a love of poetry … She taught Yeats especially well and inspired some memorable readings.’ In a half-yearly assessment she put her son top of the class in English. ‘Interesting work,’ she wrote. ‘Has quick understanding but lacks some precision in written work.’

Those who have read The Autobiography of My Father will know that it didn’t end well professionally or maritally for Trevor Edmond; and his daughter, Rachel, chose a park near the family’s Heretaunga home to die, a source of deep sadness for Edmond which he articulates looking at a photograph taken of him and her in a Wellington restaurant: ‘Bright-eyed, good-looking both of us; but there is a residue uncertainty in her expression that is desolating to see now.’

His affection for father is also palpable; he writes of working with him in the garden: ‘I am never happier than when I spend time with him.’ But he’s also his mother’s ‘green-eyed boy’, one of our better prose stylists. There is much to The Dreaming Land that I haven’t touched upon because the review’s opening paragraph dictated its course. Suffice to say that it’s a top-shelf evocation of a New Zealand childhood and adolescence, up there with Dan Davin’s Southland stories.